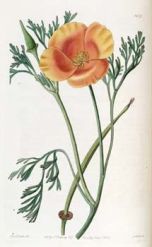

Exploring the Biogeography and Cultural Use of the California Poppy (Eschscholzia californica)

and Other Botanical Species of the Antelope Valley Poppy Reserve

by Christie Ford

I INTRODUCTION

Various research has been published about the California poppy’s characteristics, life-cycle, cultural significance, and biogeographic range. However, few publications focus on the poppy’s origin, or its ecological and cultural contexts, especially as it is reflected from Native American perspectives. This provides an opportunity study the California poppy and local species by conducting a comprehensive survey of biogeography, biology, and cultural-historical significance.

Description, Range, and Life Cycle of the California Poppy

Characterized distinctively by its bright orange flower, E. californica grows in Southern California and is common up to 4,000 feet above sea level, spanning the region from the southern Mojave Desert to the Colorado Desert. It thrives along the west coast of the United States and Baja California, extending as far north as the southern portion of Washington state. The California poppy can also be found in portions of the American Southwest, including Nevada and New Mexico (PSU 2014).

Varieties of poppy did not arrive in South America until the mid-19th century and early 20th century (Leger and Rice 2003), when poppy seeds were accidentally mixed among alfalfa seeds, which were exported from California to Chile. In addition, people may have deliberately introduced the poppy as a decorative variety. Thanks to climatic similarities between Chile and California, the poppy naturalized quickly in its new environment.

Taxonomic information for Eschscholzia californica

| Kingdom: PlantaeSubkingdom: Tracheobionta – Vascular plantsSuperdivision Spermatophyta – Seed plants Division: Magnoliophyta – Flowering plants Class: Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons Subclass: Magnoliidae Order: Papaverales Family: Papaveraceae Genus: Eschscholzia Species: californica (Tree of Life 2005; USDA n.d.) |

The California poppy (Eschscholzia californica) is pollinated and dispersed by an array of processes. Its pollination can occur via wind, insects, and other passing fauna. Its seeds are spread through ballistic dispersal, by birds (i.e., seed ingestion by quail), beetles, and, more recently humans and European Honeybees. The California poppy propagates by seed formation and dispersal. During this process, the flowers wilt and expose seed pods that are ready to burst in the summer. The seed pods dry and attach tiny seeds to other portions of the plant, making it easy to cling to or be eaten, or for the right breeze to carry it away. Seed dispersal is further facilitated through a mechanism that involves their casting in multiple directions at the slightest touch of the seed pod; even sunlight can affect sufficient heat to cause seed pods to burst. After settling in a new area, E. californica germinates readily and self-sows toward late summer or the start of fall. By the following spring, several generations of poppy would have germinated (Benson 2014).

II FIELDWORK

The Antelope valley is home to some of the most culturally and biologically representative plants in Southern California, including the California poppy. For this reason, the yearly wide-scale blooming of the California poppy on the Antelope Valley Poppy Reserve in Lancaster, California provided a chance to investigate its biosphere at the peak of the season, and to learn about the poppy’s role in the ecosystem.

In February of 2014, I made my first trip to the Poppy Reserve. Conditions were not ideal for study at the time, as a record-breaking drought in Southern California had just begun, and there had been no recent sightings of the famous orange blooms, as yet. Intense wind swept hard the dry hills that stretched into low desert flats. Vegetation appeared sparse and desiccated. Though I did encounter traces of fauna, including rabbit tracks and an instance of dried coyote scat, the terrain seemed uninhabitable.

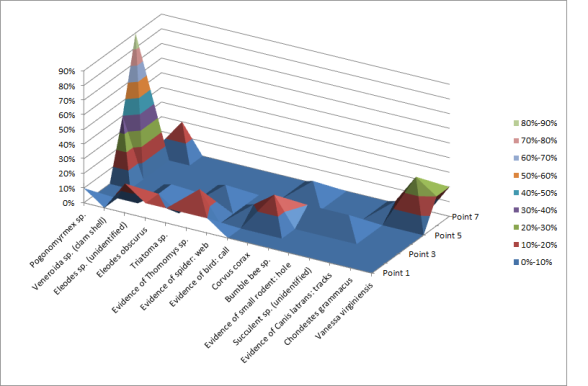

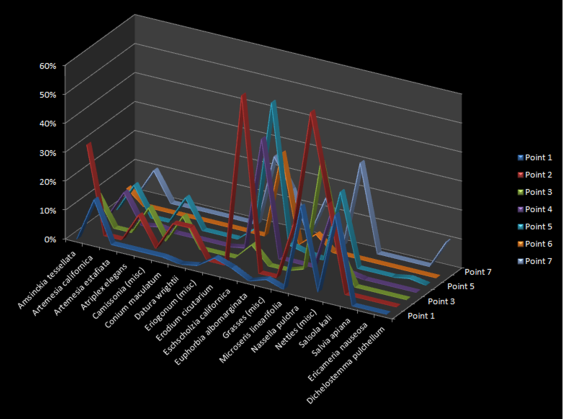

Another attempt to conduct a field survey at the Poppy Reserve took place on April 12, 2014. The survey employed a 372-meter pedestrian transect spread among seven points with a mean interval of roughly 51 meters. At each point, biological and geological data within a range of one meter were gathered, identified, and analyzed. The transect was restricted to the visitors trail, in compliance with Antelope Valley Poppy Reserve’s policy.

This second adventure to investigate E. californica revealed the unique and truly vibrant biosphere which exists in this region of the western Mojave Desert. Additionally, the vegetation was thriving and a locally beloved star, the California poppy, was in full bloom. The area was now crawling with darkling beetles and tourists alike. Despite a high rate of human disturbance in the area, I managed to collect a wide range of field samples. The link below provides access to a downloadable Google-maps file which highlights the path and data-collection points of the transect.

https://productforums.google.com/forum/embed/#!topic/gec-member-centric-locations/ZiFpEmSsMFg

Evidence of fauna include sightings of: a member of the Triatominae subfamily, or “kissing bug”; two Painted Lady butterflies (Vanessa cardui); two lark sparrows (Chondestes grammacus); several darkling beetles including the “mating” Eleodes variety; one or more unidentified bee species including a bumblebee; gopher holes; and coyote tracks.

Regarding my experience collecting data in the reserve, what was most impressive was the ability of winged insects to maintain flight and navigation through such strong winds, managing to do their part pollinating the flora.

The most prominent flora on site included fiddleneck (Amsinckia tessellata), redstem filaree (Erodium cicutarium), California sagebrush (Artemesia californica), fringed sagebrush, (Artemesia estafiata), Salsola kali (a Russian tumbleweed), purple needle grass (Nassella pulchra), and, of course, the California poppy (Eschscholzia californica).

Less common were Datura wrightii, white sage (Salvia apiana), rattlesnake weed (Euphorbia albomarginata), poison hemlock (Conium maculatum), Atriplex elegans, Silver Puffs (Microseris linearifolia), members of the Camissonia and Eriogonum genuses, various stinging and non-stinging nettles, and unidentified grasses.

Soil analysis concluded that the area’s geologic composition at Point 1 of Transect 2 was predominantly granite, a light olive grey with a spattering of pink and white pebbles. Rose colored granite and quartz were noted along the trail. Soil composition changed between Points 3 and 4 of Transect 2, becoming a light-brown sandy silt of roughly 5% sub-angular gravel which changed little through Point 5. Beginning from Point 6, gravel content increased to at least10%.

III CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE OF THE POPPY AND OTHER NATIVE PLANTS

My visit to the Antelope Valley Poppy Reserve’s information center yielded an interview with Ms. Marsha Niell, an expert on the California poppy. She was able to enlighten me regarding cultural uses of the poppy by Native Americans who once resided in the Antelope Valley region. Ms. Niell informed me that the Kitanemuk people traditionally rolled the poppy’s roots and placed it onto the gum for a mild narcotic effect, in addition to cooking its leaves for food. The extract of its seeds was used to relieve headaches. She also informed me that the Luiseño people were known to have chewed its petals like chewing-gum.

Additional research on E. californica provided further information about its traditional applications among other Native Californian groups. The plant was eaten as a regular vegetative dish, prepared either by boiling or by roasting, among several groups. The poppy was also valued for its medicinal properties that included calming, pain-killing, and antispastic effects, which make it an alternative for the treatment of anxiety and insomnia to this day. Unlike with the opium poppy (Papaver somniferum), however, the use of the California poppy does not lead to dependence (Mahr 2004).

In a brief correspondence with Mr. Craig Torres of the Gabrielino Tongva, he indicated that the California poppy was used as a mild sedative (Pers. comm. 2014). The Tongva (Gabrieleño) people referred to the plant as Mekachaa and used its root to treat tooth and stomach ailments. In addition, scrapings from the stem were applied to the navel of newborns for faster healing, and boiling the poppy allowed the creation of a salve to kill lice; the Costanoans also used the poppy in the same application. In addition to medicinal uses, the pollen of the poppy was used as a facial cosmetic among various groups as well (Mahr 2004; Swimmer 2014). The Cahuilla also valued the plant for its sedative properties, using the whole plant as mild a sedative for babies.

The Chumash people are known to have actively cultivated the California poppy for uses including food, cosmetics, as a sedative, and possibly to cure urinary-tract infections, as noted by J.D. Adams Jr. and Cecilia Garcia, authors of Healing with Medicinal Plants of the West (2005). Adams and Garcia also claim that the Chumash people traditionally created a poultice from the poppy’s seeds, which were used to stop breast milk (2006). Michael Moore, author of Medicinal Plants of the Pacific West, calls the California poppy an “effective herb for use with anxiety” and goes on to mention its ability to induce relaxation.

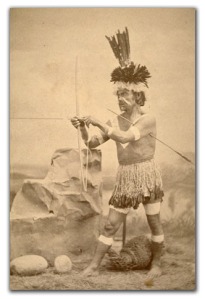

Photos courtesy of santaynezchumash.org

Additional research was conducted on traditional uses of nearby plants which grow in the reserve among the California poppy. One of these, the California Sagebrush, known as Pawots to the Tongva, was used as a medicinal tea to treat menstruation and other issues pertaining to women’s health, and played a large role in purifying rituals for girls and women. It was also used to remedy toothaches, headaches, and stomachaches by the Tongva, the groups in Mendocino County, among others (Mahr 2004; Swimmer 2014).

White sage was also prominent as a medical and dietary staple among Southern Californian Native American tribes for both its pungent scent and calming properties, which can soothe upset-stomach as well as anxiety. The Tongva called it Kasili, and used it as a ceremonial purifying plant and medicinal herb. When smoked, it treated bronchial problems; its seeds were ground into a meal serving as an anti-inflammatory eye balm; tea was made to promote women’s health. Hunters also used it to mask their own scent from animals (Swimmer 2014).

The nettles were used as a part of a Kitanemuk rite of passage for girls at the time of their first menstruation. During this time, a girl’s mother would thrash her with the nettles. This process was followed by both a bath and a drink of hot water with pounded Artemesia estafiata, the fringed sagebrush. The girl would then be painted red with white spots (on the face and upper torso) and with black stripes (upon the cheeks) by another woman chosen and paid by her mother. This intense and rigorous rite of passage was not complete until the girl had afterward run between two rocks placed at an interval of about 150’ as a specially selected, indefatigable woman gave chase. After this, the girl would be isolated with an elderly female relative for four months in a hut which her father had built. Male relatives would bring firewood to this hut, which contained a fireplace, as nights in this region can be very cold. The girl was allowed only warm food and water, and would be forbidden to bathe or eat meat, fat, chia, or salt. The girl was only permitted to exit the hut to relieve herself, during which time her head was covered. Looking at others was forbidden during this rite. At the end of the four-month period, the girl would finally be bathed by her mother and reincorporated into the community. She would have to lay face-down on a bed of the nettles for three days at the end of her first regular menses, using a wooden or abalone shell scratching stick (Blackburn and Bean 1978:565).

Sacred datura (Datura wrightii) is relatively common in the Antelope Valley, and was culturally significant to the Salinas, the Tongva (who called it manit), the Chumash(who called it momoy), and theZuni peoples. The last of these, the Zuni, traditionally made an anesthetic and narcotic powder of its root, as well as ground its flower and root together into a paste for a poultice to encourage healing in wounds (Stevenson 1915:46-48). The Zuni also used it for religious and other cultural purposes, including rain-bringing and determining guilt or innocence in cases of robbery. Having hallucinogenic properties, it was used by many Southwestern and Californian tribes in rites of passage. The Kitanemuk and the Chumash gave solutions of water and the seedpods and roots of Datura to pubescent boys after a fast, which would allow them access to magical powers through the supernatural dreams it yielded. In the Kitanemuk culture, the credit for these magical dreams was given to an a’atsiounast, or a “dream-helper,” usually represented by an animal. The potentially lethal toxicity of this plant would induce a three-day coma, if not death, after which the boy would be given a lump of tobacco to place on his gums and prompted by the captain, or pinihpa,to tell of possible symbols seen in the dreams, especially animal apparitions. These would be considered the boy’s animal helper, and the pinihpa would then accompany the boy for a session of prayer in a sacred location in the hills. With them, they would bring baubles such as seeds, beads, down-feathers, and tobacco as offerings to the animal helper. This rite was not performed on girls. The boys would also be isolated in a hut and forbidden to bathe or eat meat, but for only one month, and without the nettle treatment.

E. californica’s most local relative, the tree-poppy (Romneya coulteri), often goes unrecognized as it is dissimilar in structure. This species also has a seat in Native American folklore, albeit post-colonial in origin. It is named after the Chumash tribal leader, Matilija. As the story goes, Matilija lead an attack on the Spanish to rescue his kidnapped daughter, Amatil, who had been taken to Mission San Buenaventura, but was injured in battle alongside Amatil’s lover. Amatil survived, only to find her lover gravely injured. She took him to a hill in hopes of saving his life, but failed. The entwined corpses of the two lovers yielded an instance of the tree-poppy, the flowers of which represent Amatil’s pure tears of love, and her golden heart. The species has since been seen by some as a protector of the dead (Gilmer 2003; Schmidt 2012).

III Exploring Possible Origins of the California Poppy

Data gathered from woodrat middens suggests that E. californica has lived on the continent for tens of thousands of years. In fact, E. californica seems perfectly cut out for life in the Antelope Valley. It is only able to grow in certain areas of Southern California exhibiting the unique climate and biosphere found only there. In contrast, the ability to collect, keep, and transfer seeds among human beings has a history as old as that of agriculture itself. At first glance, the likelihood of seed-dispersal at the hand of immigrating humans might seem a reasonable theory to explain E. californica’s introduction into in North America. However, the likelihood of these poppy seeds rafting to North America from Asia does not seem all that much less likely than humans having brought them across and handed them down as heirloom seeds on their migrations into North America.

Though these may appear to be plausible suggestions for explaining to the means of dispersal for the California Poppy, evidence suggests that it is very unlikely that either human animal migrations alone would have been able to facilitate this plant’s trans-Pacific dispersal into California. There are many crucial issues with both of these theories.

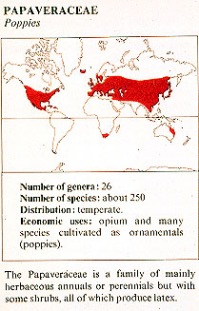

If the California poppy is not your subject of expertise, it can be easy to make the mistake of assuming that poppies originated in Asia (as I did). Although that may be true for some members of the Papaveraceae family, it appears quite likely that E. californica was an endemic development on North America since before the new and old worlds drifted apart. This is because poppies and their relatives have enjoyed an almost global geographic dispersal since well before humans began cultivating them. Additionally, the lengthy periods of time it would take for humans or migrating animals to cross the icy land-bridge connecting Asia and North America during the last Ice Age would have ensured the expiration of its seeds, which last only ten years.

As for the California poppy itself, it has been living in Southern California since before anyone can remember. In fact, it is a member of one of the most ancient known angiosperm classes, on earth: Magnoliopsida. Its dispersal takes place through many avenues including wind, ballistic, and animal dispersal. However true it may be that people tend to spread and cultivate seeds; this is a relatively recent phenomenon facing the age-old species of E. californica. Actually, research on the biogeography of E. californica is restricted by a limited body of palynological and fossil evidence, most of which was derived from woodrat middens. The small number of fossil collections is as such due to the dry properties of the soil to which E. californica is restricted.

Gilbert Ramos, field scientist and anthropology instructor at Pasadena City College, is doubtful that the poppy was brought to North America at the hand of ancient immigrating peoples. Assuming that the poppy family did originate in Asia, Ramos states that it is far more likely that the plant may have rafted or been brought to North America by way of sea birds. He explained that the theory about E. californica’s spread to North America from Asia before the continents drifted apart would seem unlikely if the poppy’s true origin actually was in Asia. This is because the Asian and North American continental plates have always been greatly distant, even when Pangaea was united. However, the hypothesis of the primeval poppy’s dispersal by way of continental drift would seem sufficient if the poppy family already inhabited a vast range (spanning across three continents – as did its wild-type ancestor, the Ranunculae), before the tectonic plates drew the continents apart.

Pangaea and continental drift.

To get a clearer picture of the California poppy’s possible origin and geographic dispersal, I was honored with the privilege of corresponding with Dr. J. Curtis Clark, Professor Emeritus of Biological Sciences at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. From his decades of research on the subject of the California poppy, he has developed well-supported inferences regarding the poppy’s origin. He provided strong evidence supporting the claim that the place of origin for E. californica is North America.

The last Ice Age, Clark explains, did not have as great an impact on the California poppy’s family or territory as it did on the rest of the world. According to Clark, there is little to no evidence of disturbance from the Ice Age on the poppy family of Papaveraceae. The facts reveal that E. californica suffered neither freezing conditions nor cutting glaciers all through the Pleistocene epoch. He mentioned that the pollen of E. californica is relatively heavy, and so depends on dispersal by insects; more so than

by way of the wind. Clark also suggested that any palynological lacustrine records from local dry lake beds, such as Rosamond or Rogers Dry Lakes, could be as old as 26,500 and 19,000–20,000 years, a time when the poppy’s range spanned the breadth of the Mojave desert. There is little to no known evidence regarding the poppy’s origin prior to this time-period, the Last Glacial Maximum.

There is sufficient evidence to support the claim that the California poppy has ranged Southern California prior to human immigration into North America by Paleoindians. In our correspondence, Clark presented several lines of evidence for the endemic development of E californica in western North America. First, the most basic evidence for the California poppy’s origin in the western United States is that all of its other relatives can also be found in western North America.

Secondly, Clark postulates that there is no record of the existence of E. californica, or any poppy, in Eurasia before 1820, and that species cultivation in that region was not widespread until the 1840s. Furthermore, California poppies are not common in Mediterranean Europe, where the climate is very similar to that of California. In the Mediterranean climate zones of Australia and Chile, poppies are considered to be weeds, although local plant varieties far outnumber them.

Clark also purports the unlikelihood that the California poppy originated in northeast Asia or northwest North America. This is because, in addition to the fact that the California poppy was not reported anywhere in Eurasia prior to 1820, the climate during the Last Glacial Maximum could not provide the appropriate environmental conditions to support any population of poppy. And since poppy seeds could remain dormant only up to a decade before expiring, the continuation of their population would have required occasional successful germination.

Traditional use of the plant exclusively among Native American groups that share the poppy’s geographic range also strengthens the argument for a western North American development of the California poppy. Native American groups in California and Baja California have traditionally used the Californian poppy for a variety of purposes, alongside other native California plants. However, Clark points out that Native American groups outside of California, such as those in Nevada or New Mexico, have not been reported to have incorporated the use of the California poppy in traditional practices, or at least as extensively as the Californian groups, which may indicate that the poppies are a relatively later development in those areas. Lastly, Clark says, close relatives of genus Eschscholzia, Hunnemannia and Dendromecon, are also North American in origin, providing greater evidence for the original development of Eschscholzia californica in western North America.

In search of further evidence of Native American activity in this region of the Mojave desert, I paid a brief visit to the Calico Early Man site, located roughly 150 kilometers west of the Antelope Valley Poppy Reserve, which was generally purported to be of interest in terms of cultural and historical information about early settlers in the region. I conducted geological analysis on rocks collected along the perimeter of the site. On these, a lithic analysis was conducted by Mr. Michael Kay, an archaeologist at Applied EarthWorks, Inc., to determine whether they presented evidence of human activity. The geologic samples from the Calico Early Man Site revealed neither an indication of tool-use, nor any other manner of human affect.

IV Conclusion

Evidence in favor of the claim that E. californica is truly endemic to western North America is strong. We may conclude that it has probably been thriving on the North American continent since well before the Last Glacial Maximum, and has certainly gained great significance in terms of human culture since prehistoric times.

References:

Adams, J. D., and C. Garcia

2005 Healing with Medicinal Plants of the West: Cultural and Scientific Basis for Their Use. Abedus Press

La Crescenta, California.

2006 Women’s Health Among the Chumash. Evidenced Based Alternative Medicine 3(1): 125-131.

Benson, P.

Do Poppies Spread? Electronic document, accessible via http://www.ehow.com/info_8465557_do

poppies-spread.html, accessed 24 April 2014.

Blackburn, T. C., L. J. Bean

1978 Kitanemuk. In Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 8, California. William C. Sturtevant,

general editor, Robert F. Heizer, volume editor, pp. 564-569. Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C.

Clark, J. C.

2014 Personal communication, email correspondence, 11 March 2014.

Gilmer, M.

2003 A Beautiful Flower Arising from an Old California Legend. Electronic document, accessible via

http://www.elkharttruth.com/news/2003/12/21/A-beautiful-flower-arising-from-an-Old-California

legend.html, accessed 23 April 2014.

Leger, E. A., and K. J. Rice

2003 Invasive California poppies (Eschscholzia california) grow larger than native individuals under reduced

competition. Ecology Letters 6:257-264.

Mahr, S.

2004 California Poppy. University of Wisconsin, Madison. Archived electronic document, accessible via

https://web.archive.org/web/20100306184755/http://www.hort.wisc.edu/mastergardener/Features/flowe

s/CA%20poppy/CA%20poppy.htm, accessed 24 April 2014.

Moore, Michael

2011 Medicinal Plants of the Pacific West. Museum of New Mexico Press, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Niell, M.

2014 Personal communication, verbal interview, 12 April 2014.

Pennsylvania State University

2014 The Floral Genome Project: Eschscholzia california. Electronic document, accessible via

http://www.floralgenome.org/, accessed 26 April 2014.

Ramos, G.

2014 Personal communication, verbal interview, 10 April 2014.

Schmidt, R

2010 Legends of Chief Matilija. Electronic document, accessible via

http://newspaperrock.bluecorncomics.com/2010/03/legends-of-chief-matilija.htm, accessed 23 April 2014.

Stevenson, M. C.

1915 Ethnobotany of the Zuni Indians. Bureau of American Ethnology, 30th Annual

Report. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Swimmer, D.

2014 Medicinal Garden. Loyola Marymount University. Electronic document, accessible via

http://academics.lmu.edu/cures/discoverypark/medicinalgarden/, accessed 24 April 2014.

Torres, Craig

2014 Personal communication, email correspondence, 3 May 2014.

United States Department of Agriculture

n.d. Classification: USDA Plants. Electronic document, accessible via

https://plants.usda.gov/java/ClassificationServlet?source=display&classid=Magnoliidae, accessed 23

April 2014.

Unless otherwise stated, photos by Christie Ford, 2014. Of these, feel free to use and redistribute.